That makes no sense. But as companies scrap the paid-time-off quota, this eye-popping perk ends up doing more for bottom lines than tan lines.

“The United States is the only advanced economy in the world that does not guarantee its workers paid vacation days and paid holidays,” says John Schmitt, senior economist and co-author of a recent Center for Economic and Policy Research study. The US also lacks legislation defining a work week’s maximum length, has no paid sick leave requirements, and no laws to guarantee maternity or paternity leave.

Without a legally mandated number of paid holidays, workers presume to appear less dedicated—or more, replaceable—if they take a proper vacation, and every year, the majority of US workers leave several paid days unredeemed. And the American state of vacay shows little sign of improvement.

In response—and hoping to seem altruistic—some organizations have implemented unlimited paid time off (PTO), touting the policy as the ultimate work perk. Unlimited vacation? Well, yes. But while attractive in theory, these policies often end up serving company interests more than employees.

As far back as 1983, Americans averaged 20 days off a year. According to Project:Time Off, that number had dropped to 16 days by 2014. Only in the last year has it slightly increased to 17 days. In 2017, 52 percent of American workers did not take any time off, a national tally of 705 million unused days, up from 662 million days the year before. On top of this, 85.8 percent of men and 66.5 percent of women reported working more than 40 hours per week.

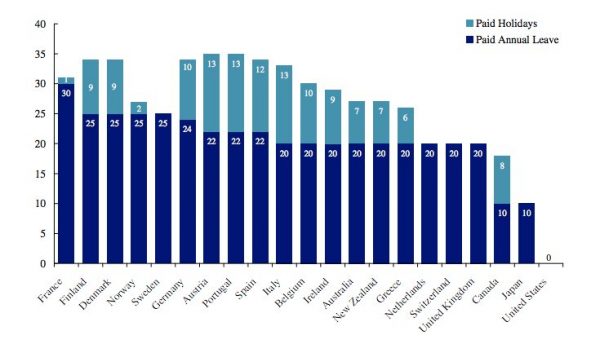

Conversely, the European Union guarantees minimum 20 paid days per year, excluding bank holidays, with many specific countries offering even more generous time-off policies.

John Schmitt’s CEPR study found the current number of paid vacation days for US workers, on average, is 10 days.

Is the American work ethic to blame for such discrepancy, or is it our self-inflicted culture of overwork, and making ourselves constantly available for work? France recently implemented a “right to disconnect” law, which, as of January 2017, prohibits staff from sending or answering emails outside of set work hours. Meanwhile, according to Project:Time Off, job issues had the most influence on why Americans weren’t traveling, be it heavy workloads, lack of colleague support, or fear of being replaced.

Aiming to adopt a more European attitude, organizations like Netflix and LinkedIn implemented unlimited PTO, and they’ve made for happier and healthier employees. At Nav, a business credit management firm, CEO Levi King did so because, “even if it’s just symbolic, it reinforces the fact that we hired you because you seem like the type of person who can handle a little freedom.”

King argues that unlimited PTO “translates into more gratitude for the job and an even stronger, deeper commitment to the company.” However, “unlimited PTO only works if you’ve hired smart, hardworking people who’ve bought into the vision, mission and values of your company.”

Still, 40 percent of employees report being unsure their company wants them to use all the vacation time they earn. Workplace optics precede the beach for many US workers.

To solve this, you need the kind of company culture building nurtured at giants like Facebook, Amazon, Netflix, and Google. Tech’s big four, known collectively as FANG, have built employer brands that attract talent almost as fast as they generate profit. Not many companies outside Silicon Valley maintain culture where unlimited PTO wouldn’t be seen as antithetical, even blasphemous. Portland, maybe. But with a collective worth valued at more than $1.5 trillion—about the same as the Russian economy—the FANGs are well positioned to reward hard-working employees with these kinds of perks.

But who says unlimited PTO’s a perk, anyway? One of the strongest arguments against is that companies benefit more than employees.

What?

Yep. By nixing holiday totals, businesses are no longer required to pay out unused vacation hours otherwise accrued through traditional policies, saving organizations considerable costs during times of employee turnover.

Last year, Americans forfeited 212 million days, equivalent to $62.2 billion in lost benefits. This means employees effectively donated an individual average of $561 in work time to their employers. That’s not exactly a worker perk.

The solution? Shorter work weeks. New Zealand trust and estate management firm, Perpetual Guardian, experimented with 32-hour work weeks during March and April 2018, while continuing to pay their 240 employees their regular salary. Two researchers studied the effects of this experiment and found that:

- Employees reported a 24 percent improvement in work-life balance.

- Meetings were reduced from two hours to 30 minutes.

- Employees created “do not disturb” signals to notify their colleagues they needed to work without distraction.

Above all, employees remained productive their whole time in the office.

Jarrod Haar, an HR professor at the Auckland University of Technology, and one of the researchers who worked on this project, told the New York Times, “Their actual job performance didn’t change when doing it over four days instead of five … supervisors said staff were more creative, their attendance was better, they were on time, and they didn’t leave early or take long breaks.”

A similar experiment took place in Gothenburg in 2016, when Swedish nursing home Svartedalens mandated a six-hour day without pay cut. City officials saw employees sharply reduce absenteeism, improve health, and complete the same amount of work—or even more.

So far, no US firms have gone in for shorter work-days or -weeks, but both businesses and employees stand to gain from more generous time-off policies.

“Companies encouraging vacation may realize it is a competitive advantage,” Schmitt claims. “Employees who feel supported in taking vacation are happier with their job, company, relationships, and health, allowing them to bring their best selves to the job when they are on the clock.”